Consideration of Alternatives

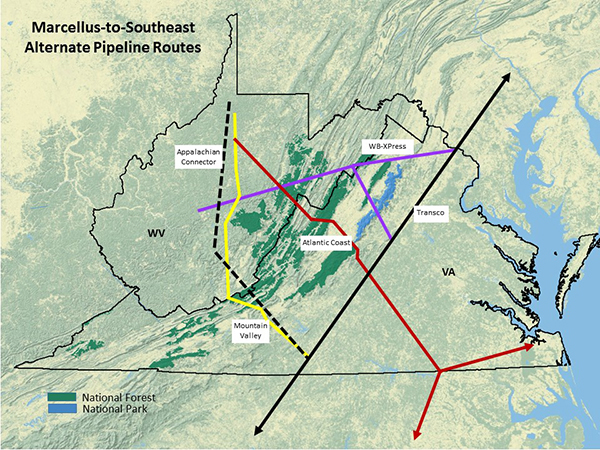

We face proposals for construction of three 42-inch pipelines for moving Marcellus shale gas from western West Virginia to Virginia and the southeast. These pipelines would be the largest ever built in this region.

These pipelines will require excavation of 125-foot-wide construction corridors over multiple steep-sided forested mountains. They will require heavy-duty transport roads and staging areas for large earth-moving equipment and pipe delivery. They will require extensive forest clearing, surface compaction, blasting through bedrock, and excavation through streams, wetlands, and riparian areas. They will cross hydrologically sensitive karst landscape and water-supply recharge areas. They will cross national forest and other public conservation lands, as well as farmland and developed communities. They will require the use of eminent domain on an unprecedented scale.

Although the National Environmental Policy Act requires analysis of alternatives, the initial information submitted to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and the Forest Service by the pipeline developers has raised concerns that analysis of alternatives to proposed pipeline construction will be both incomplete and potentially self-serving. Conservation and community groups in the central Appalachian region have therefore initiated their own analysis to compare the environmental and human costs of pipeline alternatives.

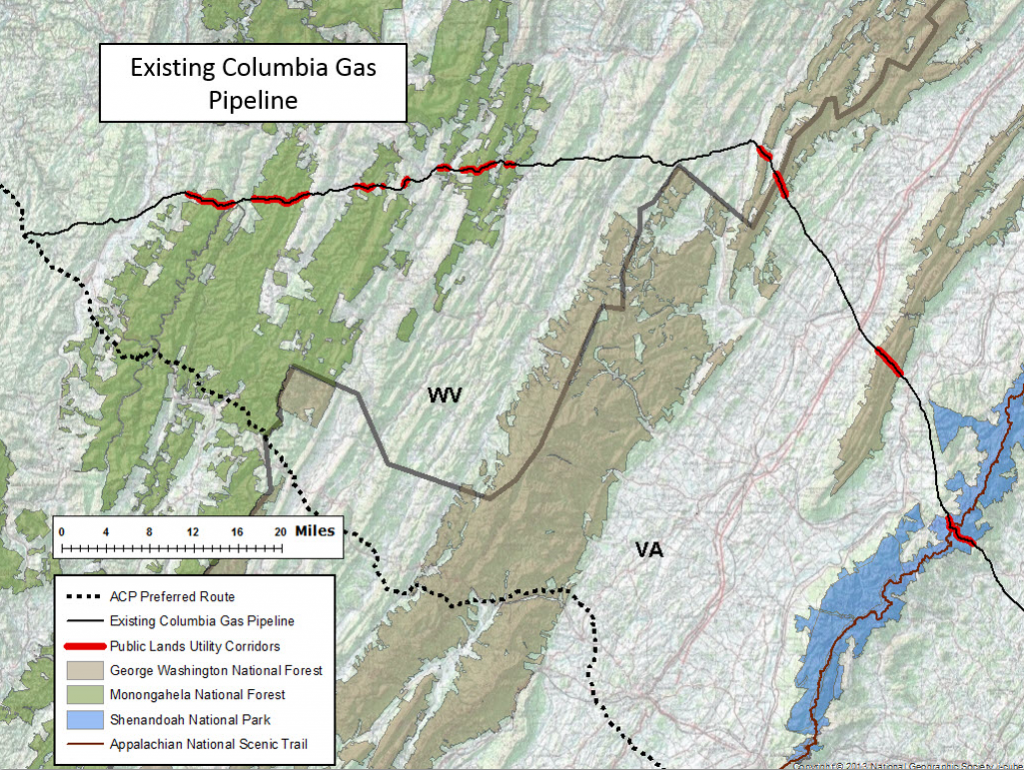

The existing Columbia Gas pipeline intercepts the proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline to the west and the Transco interstate pipeline to the east.

The objective of this citizen-led analysis is to find alternatives that minimize impacts and risk to public conservation lands, high-quality streams, water supplies, historic resources, farms, and residential areas. In particular, we seek an alternative that minimizes confiscation of private property through eminent domain.

While the pipeline developers claim to have evaluated alternative routes, the limited information available to the public and the regulatory agencies suggests that any such evaluation was strictly pro forma, and that selection criteria were vague and inconsistent. The developers, moreover, have been nonresponsive to citizen group requests for detailed route information. As a result, citizen groups have asked for delays in the scheduling of public comment periods and regulatory decision making until detailed information about route alternatives has been made available in a reasonable timeframe.

At this point, with the limited information that is available, our recommendations concerning alternatives will be limited to generalities. Given our objective to avoid impacts and risks to both natural and community resources, and to minimize the use of eminent domain, the only known acceptable alternatives involve the use of the existing pipeline infrastructure or co-locating with existing utility or other public corridors.

The use of the existing pipeline infrastructure merits serious consideration.

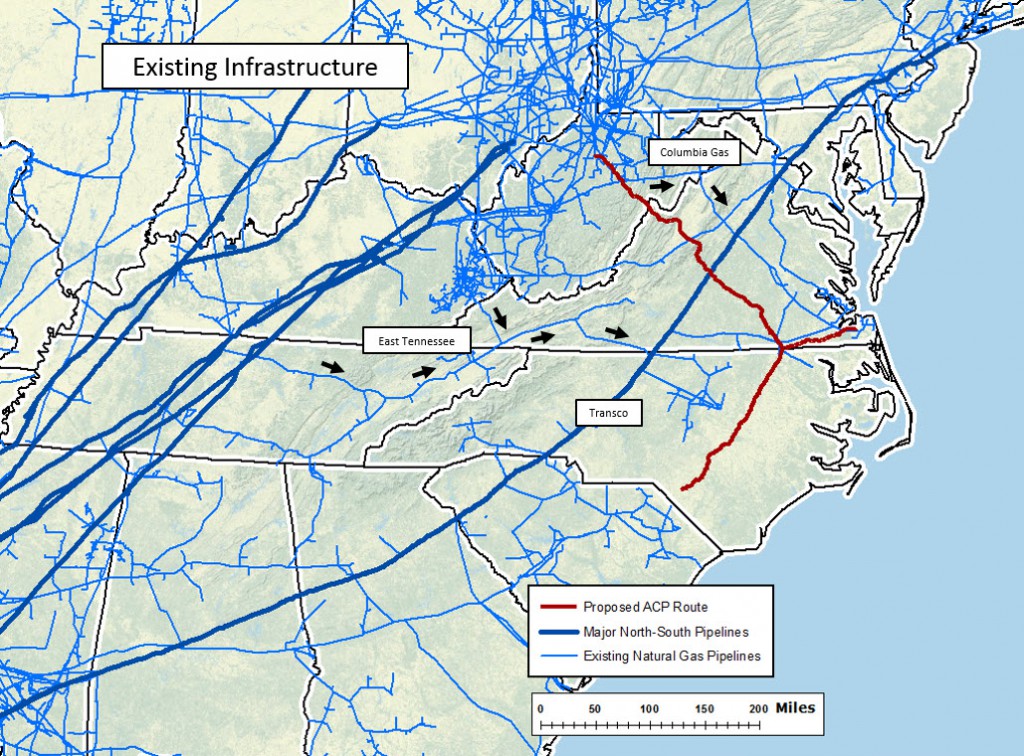

There are many existing pipelines that follow a general trajectory from the Marcellus drilling area to the proposed delivery points in the southeast. The U.S. Energy Information Administration reports that many pipelines have seen a significant decrease in usage in recent years, and that a number of the major north-south pipelines dedicated to delivering gas to the northeast will become bidirectional and thus available for delivering gas to the southeast.

Use of existing utility corridors across the central Appalachian Mountains would certainly be less damaging than the creation of new corridors. The options include co-location with existing pipelines, electric transmission lines, and interstate highways.

The possibilities for moving gas from west to east using existing pipeline corridors include use of the East Tennessee corridor in southwest Virginia or use of the Columbia Gas corridor in northwest Virginia. The Columbia Gas corridor, for example, extends across West Virginia and into Virginia, intercepts the major Transco north-south pipeline corridor and continues on to the southeast before ending close to one of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline delivery points near Portsmouth, Virginia. This pipeline corridor would clearly be unacceptable if it were proposed today. It crosses the Monongahela and the George Washington National Forests and the Shenandoah National Park. But, like the East Tennessee pipeline, it is already there, and thus its utilization would result in less overall environmental impact than a new corridor.